Urbanismo Miliciano in Rio de Janeiro: mudanças entre as edições

Sem resumo de edição |

Sem resumo de edição |

||

| (4 revisões intermediárias por 2 usuários não estão sendo mostradas) | |||

| Linha 1: | Linha 1: | ||

Autores: Leandro Benmergui'<nowiki/>''<ref name="Leandro Benmergui">(Ph.D. University of Maryland) is an assistant professor in the Department of History at Purchase College, SUNY; he chairs the Department of Latin American Studies and is the director of Casa Purchase, an Outreach | |||

Autores: | Center for Latin American Studies. His work is on the transnational aspects of urban and housing policies in Latin America. leandro.benmergui@purchase.edu</ref>''' e Rafael Soares Gonçalves<ref>(Ph.D. Université de Paris VII) is an associate professor in the Department of Social Work at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica-Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ), Brazil. He is the coordinator of the Laboratório de Estudos Urbanos e Soioambientais (LEUS) and editor of the journal O Social em Questão. He is the author of | ||

Center for Latin American Studies. His work is on the transnational aspects of urban and housing policies in Latin America. leandro.benmergui@purchase.edu</ref>''' e | Favelas do Rio de Janeiro: História e Direito (2013). rafaelsgoncalves@yahoo.com.br</ref><ref>Extraído de: [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10714839.2019.1692986?needAccess=true& NACLA Report on the Americas, 51:4, 379-385] | ||

Favelas do Rio de Janeiro: História e Direito (2013). rafaelsgoncalves@yahoo.com.br</ref> | |||

</ref> | |||

Extraído de: [https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/10714839.2019.1692986?needAccess=true& NACLA Report on the Americas, 51:4, 379-385] | == Intro == | ||

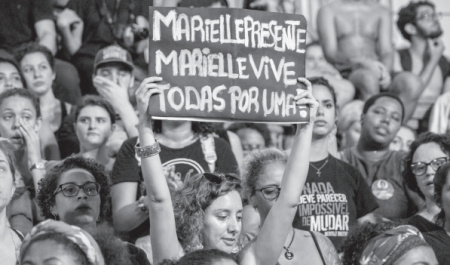

<blockquote><p style="text-align: | <blockquote><p style="text-align: justify;">''<span style="font-size:10.0pt"><span style="line-height:107%">Rio de Janeiro’s poor communities face increasing vulnerability as armed groups expand control of entire neighborhoods, operating illicit businesses from protection rackets to real estate, with dire consequences for local residents living under a violent parallel state.</span></span>''</blockquote>[[File:Muzema 01.jpg|thumb|right|top|550px|The scene in Muzema, Rio de Janeiro, after buildings collapsed in April 2019. (CLAUDIA MARTINI/FLICKR)]]In April 2019, two buildings collapsed in the community of Muzema, Rio de Janeiro, killing 24 people as a result of the heavy rains that hit the city during the summer. Sixteen other buildings with similar characteristics remain at risk of collapse. The municipal government has debated between eviction, demolition, and a dangerous status quo, given the appeal filed by the residents of the complex to prevent their removal. The deaths, material damage, and widespread chaos in the city as a result of the storms revealed the negligence of the municipal, state, and federal governments and the lack of consistent urban and housing policies, especially for the most impoverished sectors of the city. The Muzema tragedy, however, was not the result of natural causes: it was a product of the actions of Rio de Janeiro’s milícias, namely their urban practices and their real estate ventures. Muzema is a favela located in the west of Rio, a region under the territorial control of these milícias—parastate groups composed of police, military firefighters, and active or retired correctional officers who assert control over poor communities. The milícias are in the process of expanding and have already taken over many of the city’s favelas. They are authoritarian, and they suppress neighborhood associations and repress dissent through intimidation and murder. They offer security to residents, especially against drug trafficking and crime, as the basis for their legitimacy. In addition to these “protection” services, their businesses include selling gas cylinders, cable TV and internet, transportation services, and real estate, among other ventures. Territorial control provides them with a wealth of voters that has allowed them to elect representatives to all levels of executive power in the municipal, state, and national governments, institutionalizing their influence and guaranteeing impunity. Police investigations have linked members of the milícias with the brutal March 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, along with her driver Anderson Gomes. At the time of her death, the councilwoman, a prominent Black and LGBTQI+ activist of favela origin, had been investigating milícia practices in the favelas and their connections with politicians and members of the government. Today, Rio de Janeiro is a case study in dystopian radicalism: the milícias are advancing violently and with impunity on the urban space and daily life of Rio residents, becoming part of the state structures at the municipal, state, and federal levels, seriously threatening democratic life in Brazil.</p> | ||

== Milícia History == | |||

= Milícia History = | |||

<p style="text-align: justify;">[[File:Marielle01.jpg|thumb|left|top|450px|People gather in memory of Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro the day after her March 14, 2018 murder. (BERNARDO G./FLICKR)]]The organization of para-police groups in Rio began at the end of the 1950s with the creation of the Grupo de Diligências Especiais at the initiative of the police chief of Brazil’s then-capital city. Its primary mission was the execution of criminals. Known as Esquadrões da Morte or death squads, these groups were composed of active and retired police officers. The Esquadrões extended their presence through the Baixada Fluminense on Rio’s periphery, an area that grew rapidly as a result of the allotment of lands—in many cases of dubious origins—as migrants arriving from the interior did not have access to housing in more central areas of the city. These extermination groups, known as polícia mineira, charged vendors and small business owners for protection and carried out contract killings, as sociologist Michel Misse has noted. They also had links with community and political leaders, such as Tenório Cavalcanti, the famous leader of the Baixada known as the “man in the black cape.” It was said that he hid a German machine gun nicknamed Lurdinha in his coat. In the 2003 book Dos barões ao extermínio: uma história da violência na Baixada Fluminense, sociologist José Claudio Souza Alves explains that the elimination of the rule of law and the advance of state terrorism during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship paved the way for the consolidation of death squads linked to the military police, a force created in 1967. Relations developed with other civil and political leaders who would take up positions within the structure of the state once democracy returned. The current milícias emerged based on this model. They exercise ironclad military and territorial control over the favelas located in Rio’s periphery, dominate community organizations, and extend their links with politicians and public officials, allowing them access to structures of executive, legislative, and judicial power. According to scholars Ignacio Cano and Thais Lemos Duarte, five central elements define the milícias: territorial and population control by irregular armed groups in small areas; coercion of inhabitants and local businesses; drive for individual profit; legitimizing discourses of fighting drug trafficking and establishing order and protection; and the active participation of armed state agents in positions of command. Rio das Pedras, located in Rio’s West Zone, was the first favela to fall under milícia control at the end of the 1980s. From there they expanded to other favelas of the West Zone and, later, the entire city. In Rio das Pedras, the milícia took over the residents’ association, expelling or executing its former leaders, and later it began selling its “services” to shopkeepers and the entire population of the favela. The neighborhood quickly became famous for “killing bandidos” (criminals) and ending drug trafficking. Amid a surge in drug trafficking-related violence—whether between rival factions fighting for control of the favelas or between criminal groups and the police—the general public, including many favela residents, received this rhetoric of security and order in the face of drug violence positively. Many perceived Rio das Pedras as an example of security, protection, and order. As Michelle Airam da Costa Chaves’s study on journalistic coverage of milícias shows, there have been no major police operations in communities occupied by milícia groups in recent years, reinforcing the idea that these groups are a “lesser evil” compared to drug traffickers. This idea spread in the 2000s as milícias advanced into other favelas and expelled the drug trafficking operations there, as Alba Zaluar and Isabel Siqueira Conceição have analyzed. In 2006, Rio mayor Cesar Maia even classified milícias as “community self-defense” groups against drug trafficking and as possible interlocutors with the state, since they were made up of former police officers. At that time, Rio was preparing to organize the 2007 Pan American Games, the first in a series of international mega-events that included the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. For the state, these milícias promised relative calm in the favelas during the events that had the city at the center of global attention. For the middle class, forever anxious about favelas and drug trafficking—despite always needing the cheap labor favela residents provide and middle-class people being the main consumers of drugs—the milícias represented a solution rather than a problem. The press generally reproduced this positive assessment. However, in May 2008, milícias from the Batan favela kidnapped and tortured journalists from the O Dia newspaper who had been investigating their actions. From that moment, the perception of the milicas shifted to being part of organized crime and compared to mafias. Together with an escalation of violence, milícia expansion into other favelas, and the diversification of their illegal businesses, this incident provoked a change. After several frustrated attempts led by the leftist representative Marcelo Freixo of the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), the Rio state legislature finally opened a parliamentary investigation into the episode. Ten years later, a Datafolha investigation in conjunction with the Brazilian Public Safety Forum indicated that milícia members are more feared than traffickers, both in the communities of Rio and in the most privileged neighborhoods of the southern Rio area.</p> | <p style="text-align: justify;">[[File:Marielle01.jpg|thumb|left|top|450px|People gather in memory of Marielle Franco in Rio de Janeiro the day after her March 14, 2018 murder. (BERNARDO G./FLICKR)]]The organization of para-police groups in Rio began at the end of the 1950s with the creation of the Grupo de Diligências Especiais at the initiative of the police chief of Brazil’s then-capital city. Its primary mission was the execution of criminals. Known as Esquadrões da Morte or death squads, these groups were composed of active and retired police officers. The Esquadrões extended their presence through the Baixada Fluminense on Rio’s periphery, an area that grew rapidly as a result of the allotment of lands—in many cases of dubious origins—as migrants arriving from the interior did not have access to housing in more central areas of the city. These extermination groups, known as polícia mineira, charged vendors and small business owners for protection and carried out contract killings, as sociologist Michel Misse has noted. They also had links with community and political leaders, such as Tenório Cavalcanti, the famous leader of the Baixada known as the “man in the black cape.” It was said that he hid a German machine gun nicknamed Lurdinha in his coat. In the 2003 book Dos barões ao extermínio: uma história da violência na Baixada Fluminense, sociologist José Claudio Souza Alves explains that the elimination of the rule of law and the advance of state terrorism during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship paved the way for the consolidation of death squads linked to the military police, a force created in 1967. Relations developed with other civil and political leaders who would take up positions within the structure of the state once democracy returned. The current milícias emerged based on this model. They exercise ironclad military and territorial control over the favelas located in Rio’s periphery, dominate community organizations, and extend their links with politicians and public officials, allowing them access to structures of executive, legislative, and judicial power. According to scholars Ignacio Cano and Thais Lemos Duarte, five central elements define the milícias: territorial and population control by irregular armed groups in small areas; coercion of inhabitants and local businesses; drive for individual profit; legitimizing discourses of fighting drug trafficking and establishing order and protection; and the active participation of armed state agents in positions of command. Rio das Pedras, located in Rio’s West Zone, was the first favela to fall under milícia control at the end of the 1980s. From there they expanded to other favelas of the West Zone and, later, the entire city. In Rio das Pedras, the milícia took over the residents’ association, expelling or executing its former leaders, and later it began selling its “services” to shopkeepers and the entire population of the favela. The neighborhood quickly became famous for “killing bandidos” (criminals) and ending drug trafficking. Amid a surge in drug trafficking-related violence—whether between rival factions fighting for control of the favelas or between criminal groups and the police—the general public, including many favela residents, received this rhetoric of security and order in the face of drug violence positively. Many perceived Rio das Pedras as an example of security, protection, and order. As Michelle Airam da Costa Chaves’s study on journalistic coverage of milícias shows, there have been no major police operations in communities occupied by milícia groups in recent years, reinforcing the idea that these groups are a “lesser evil” compared to drug traffickers. This idea spread in the 2000s as milícias advanced into other favelas and expelled the drug trafficking operations there, as Alba Zaluar and Isabel Siqueira Conceição have analyzed. In 2006, Rio mayor Cesar Maia even classified milícias as “community self-defense” groups against drug trafficking and as possible interlocutors with the state, since they were made up of former police officers. At that time, Rio was preparing to organize the 2007 Pan American Games, the first in a series of international mega-events that included the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. For the state, these milícias promised relative calm in the favelas during the events that had the city at the center of global attention. For the middle class, forever anxious about favelas and drug trafficking—despite always needing the cheap labor favela residents provide and middle-class people being the main consumers of drugs—the milícias represented a solution rather than a problem. The press generally reproduced this positive assessment. However, in May 2008, milícias from the Batan favela kidnapped and tortured journalists from the O Dia newspaper who had been investigating their actions. From that moment, the perception of the milicas shifted to being part of organized crime and compared to mafias. Together with an escalation of violence, milícia expansion into other favelas, and the diversification of their illegal businesses, this incident provoked a change. After several frustrated attempts led by the leftist representative Marcelo Freixo of the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), the Rio state legislature finally opened a parliamentary investigation into the episode. Ten years later, a Datafolha investigation in conjunction with the Brazilian Public Safety Forum indicated that milícia members are more feared than traffickers, both in the communities of Rio and in the most privileged neighborhoods of the southern Rio area.</p> | ||

= Urbanismo Miliciano = | == Urbanismo Miliciano == | ||

[[File:Vende 1.jpg|thumb|left|top|500px|A sign in the Rio das Pedras favela photographed in 2007 announces a shack for sale. (RAFAEL SOARES GONÇALVES)]]The milícia’s activities are multiple. Typically, they begin by occupying a favela and banishing traffickers. Once established, they sell protection to residents and businesses, charging security fees and ensuring control of the other areas in which they do business. Surprisingly, the milícias also divert and steal oil directly from distribution pipelines, run garbage collection operations, illegally extract sand, and conduct shrimp fishing outside the permitted period. There are reports that milícias trade narcotics directly or through agreements with certain drug trafficking factions. The real estate business is key. According to 2008 parliamentary commission investigation report on milícias, the tax on home sales varied between 10 to 50 percent of the sales’ value, in addition to the fees collected to legalize the housing or to authorize self-construction. The rapidly growing favelas offer significant profits in the informal real estate market, and the milícias have both access to the area and operational capacity. The Muzema tragedy evidenced the extent to which the milícias have invested heavily in the local informal real estate market, this time including a series of tall housing structures, a new development in the verticalization of informality. We use the concept urbanismo miliciano to describe this kind of urban intervention, which includes the illegal appropriation of public land and its allotment, mass construction of buildings, and real estate and financing operations through informal credit. Shielded by impunity or tacit consent, milícias avoid municipal controls to appropriate land and erect buildings without any supervision and without even having development plans endorsed by the relevant authorities. The lack of services and urban infrastructure, in addition to buildings’ poor construction, reproduces the vulnerability of the future “owners,” who inhabit the homes before they are finished to hedge against potential eviction or the completion of the work being blocked. Of course, this type of verticalization also occurs in other favelas, including those dominated by drug trafficking. However, the scale and logic behind the construction are different. In a large portion of the favelas, it is the residents themselves who build new floors to live in, sell, or rent, following a for-profit scheme. But they do this progressively, following a model of self-construction in accordance with the family’s needs or economic means, as anthropologist Mariana Cavalcanti has documented. From a civil engineering perspective, in many cases more construction materials and infrastructure are used than necessary. On the other hand, in the case of buildings like in Muzema, construction happens in a comprehensive way. Without any kind of urban plan, this development streamlines the construction process in a traditional way and looks to save on materials, always seeking to maximize profits. The milícia controls real estate activities and ultimately resolves conflicts between neighbors. Not all builders and sellers are necessarily members of the milícia, but they must respect the rules imposed and pay the required fees. It is very common that any and all real estate transactions be registered in the residents’ association, controlled by the milícias, through the payment of a percentage of the property value, in addition to the usual monthly rate for security services. This milícia expansion is certainly not without tensions related to the logic of a state that still must provide some kind of solution to urban problems or mediate between formal and informal sectors. The recent eradication in September 2019 of the Canal do Anil favela, for example, where the municipality intervened by strategically demolishing milícia-owned houses, demonstrated the tension between the interests of the informal real estate business of the milícia and the formal one. In this context, the role of the public defender’s office remains at a crossroads between the need to defend owners who legally purchased their properties and, in doing so, indirectly benefiting the milícia. At the same time, this year Rio’s Evangelist mayor Marcelo Crivella continued to propose further construction of housing complexes in Rio das Pedras, the first community under milícia control. These contradictions demonstrate the complexity and overlap of interests that make the question of housing and urban issues in Rio difficult to resolve.</p> | |||

= Rio’s Dystopian Model = | == Rio’s Dystopian Model == | ||

<p style="text-align: justify;">In a city where the constant fear of violence and consequent value of security have determined housing patterns of the middle and upper classes, we must consider how sectors lower on the social ladder seek the same standards. The viability of these real estate ventures also has to do with access to informal forms of credit and payment in installments, given the impossibility of accessing formal mortgage markets. The comparatively low cost of housing in the informal market also reflects the absence of both public mechanisms to control land values and public policy regarding social housing. Relying on the market as the only regulatory mechanism leads to spatial segregation, pushing affordable housing towards the urban periphery with lower costs and quality. Anthropologist Teresa Caldeira has highlighted the relationship between the illegal private security market, death squads, and the privatization of public space and ways of living. The same search for security that delineated the fortified enclaves of the elite in gated neighborhoods throughout Brazil now manifests in Rio’s favelas. The inhabitants who choose to buy a home in a building built illegally in a favela choose to pay the cost of daily control over their lives, as well as the extra fees to live in a seemingly safe and predictable place—even when, as happened in Muzema, torrential rains expose buildings’ poor construction quality and the state of constant vulnerability residents unprotected by the law must face. In addition to mourning their dead, many of the survivors of the collapse lost their economic investment and had to return to live with other relatives or friends in favelas in remote areas. Furthermore, the milícias control a large part of the housing complexes built by the federal social housing plan known as Minha Casa, Minha Vida. This project conceived the new popular neighborhoods in the image of gated middle-class condominiums. The milícias have forcibly interfered in these areas with the offer of private security, authoritatively organizing other dimensions of residents’ daily life. This cycle of violence dangerously degrades basic human rights principles and the democratic order itself. Undoubtedly, the presence of organized crime in the development of urban informality in Rio is as old as the city itself. We do not intend to argue against informality. The ways popular sectors access the city have always involved informal mechanisms. Historically, as Rafael Soares Gonçalves has argued, the origin and consolidation of the favelas were linked to the informalization of the real estate market through laws and urban codes that illegalized alternative forms of occupation and land tenure. In that way, informality is an urban planning regime through which the most impoverished sectors have achieved access to housing and the city itself. The precariousness of the rights and the vulnerability of favelas inhabitants—a product of the lack of official recognition of their existence—resulted in multiple political arrangements between residents, speculators, and local politicians, which in turn led to the formation and consolidation of these settlements, as Gonçalves, historian Brodwyn Fischer, and others have demonstrated. Although historically informality in the favelas has produced practices linked to organized crime and abuse, even in connection with public authorities, the current situation marks a qualitative change. The actions of the milícias represent a new dimension of the activities of parastate groups, whose central feature is precisely the exploitation of urban resources without clear forms of control by the state or local associations. Their presence in public power structures makes it highly likely that they will continue to establish themselves in key places of the state—at the local, state, and federal levels—and within urban space by selling their services, intimidating, and increasingly militarizing Rio’s geography.</p> | <p style="text-align: justify;">In a city where the constant fear of violence and consequent value of security have determined housing patterns of the middle and upper classes, we must consider how sectors lower on the social ladder seek the same standards. The viability of these real estate ventures also has to do with access to informal forms of credit and payment in installments, given the impossibility of accessing formal mortgage markets. The comparatively low cost of housing in the informal market also reflects the absence of both public mechanisms to control land values and public policy regarding social housing. Relying on the market as the only regulatory mechanism leads to spatial segregation, pushing affordable housing towards the urban periphery with lower costs and quality. Anthropologist Teresa Caldeira has highlighted the relationship between the illegal private security market, death squads, and the privatization of public space and ways of living. The same search for security that delineated the fortified enclaves of the elite in gated neighborhoods throughout Brazil now manifests in Rio’s favelas. The inhabitants who choose to buy a home in a building built illegally in a favela choose to pay the cost of daily control over their lives, as well as the extra fees to live in a seemingly safe and predictable place—even when, as happened in Muzema, torrential rains expose buildings’ poor construction quality and the state of constant vulnerability residents unprotected by the law must face. In addition to mourning their dead, many of the survivors of the collapse lost their economic investment and had to return to live with other relatives or friends in favelas in remote areas. Furthermore, the milícias control a large part of the housing complexes built by the federal social housing plan known as Minha Casa, Minha Vida. This project conceived the new popular neighborhoods in the image of gated middle-class condominiums. The milícias have forcibly interfered in these areas with the offer of private security, authoritatively organizing other dimensions of residents’ daily life. This cycle of violence dangerously degrades basic human rights principles and the democratic order itself. Undoubtedly, the presence of organized crime in the development of urban informality in Rio is as old as the city itself. We do not intend to argue against informality. The ways popular sectors access the city have always involved informal mechanisms. Historically, as Rafael Soares Gonçalves has argued, the origin and consolidation of the favelas were linked to the informalization of the real estate market through laws and urban codes that illegalized alternative forms of occupation and land tenure. In that way, informality is an urban planning regime through which the most impoverished sectors have achieved access to housing and the city itself. The precariousness of the rights and the vulnerability of favelas inhabitants—a product of the lack of official recognition of their existence—resulted in multiple political arrangements between residents, speculators, and local politicians, which in turn led to the formation and consolidation of these settlements, as Gonçalves, historian Brodwyn Fischer, and others have demonstrated. Although historically informality in the favelas has produced practices linked to organized crime and abuse, even in connection with public authorities, the current situation marks a qualitative change. The actions of the milícias represent a new dimension of the activities of parastate groups, whose central feature is precisely the exploitation of urban resources without clear forms of control by the state or local associations. Their presence in public power structures makes it highly likely that they will continue to establish themselves in key places of the state—at the local, state, and federal levels—and within urban space by selling their services, intimidating, and increasingly militarizing Rio’s geography.</p> | ||

= Illuminating Resistance = | == Illuminating Resistance == | ||

<p style="text-align: justify;">Unlike other Brazilian cities, such as the case of Porto Alegre or São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro has not developed a tradition of partisan urban management in recent years. In the case of Rio, the Left’s relative weakness at the municipal and state levels has to do, among other reasons, with the history of brizolismo associated with Leonel Brizola and the lack of Workers’ Party (PT) roots within municipal policy. The 1982 election of Leonel Brizola of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT) as governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro deeply influenced Rio politics. A national politician, Brizola represented the labor legacy of varguismo—the ideology associated with nationalist president Getúlio Vargas—in the years after the return to democracy. As Gonçalves and Bryan McCann have shown, Brizola pioneered large-scale urban interventions in the favelas and reorganized public education in the state by democratizing access for all social sectors. At the same time, he openly questioned police violence and rejected mão dura or iron fist policies against crime, which garnered criticism from middle-class sectors, who withdrew their support. Among Brizola’s legacies are the strong influence he exerted on the Left in Rio and in the formation of a whole generation of local politicians who, after the breakup of the PDT, migrated to other parties. Unlike other left-wing parties, such as the PT or more recently the PSOL, whose social bases are predominantly middle-class, Brizola’s PDT represented the last left party with deep popular grassroots foundations in Rio de Janeiro. The issue of violence in Rio de Janeiro, especially as the drug trafficking boom dominated public debate in the city and the state’s political agenda, impeded the potential for a more reformist leftist movement of the masses. More recently, the protests that took to the streets in 2013 against rising transportation costs and the corruption associated with organizing the Olympic Games produced political disenchantment in an era of economic and institutional crisis that would help lead to the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff. New dramatic levels of violence against the poor, injustice, and impunity paled attempts to expand rights to the city. PT initiatives reduced social inequalities, but they did not question the ongoing neoliberal project. Like a house of cards, the government abandoned many of the historical struggles for urban reform, especially after extreme right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro came to power. Despite his neoliberal agenda and heavy military presence in popular neighborhoods, Bolsonaro achieved strong support in these spaces. Widespread fear of urban violence, anger against corruption in all political parties—including the PT—and a moral discourse from Evangelical churches and the more conservative sectors of the Catholic Church fed this dynamic. Despite the current profound political crisis putting Brazil’s very democracy at risk, a new generation of more combative politicians, particularly women of color, is emerging. Although she was elected with the traditional vote of the progressive middle class, Marielle Franco of the PSOL inaugurated a new way of performing as a city counselor by enacting grassroots policy in popular neighborhoods, including areas controlled by the milícia. The attempt to silence Marielle propelled new figures to enter the political scene, with many of her direct advisors winning office as state and federal legislators in the 2018 elections. Like Marielle, they are women, Black, and favela dwellers, and they carry the political practices of the city to many popular spaces. This year, the champion samba school Mangueira honored Marielle in its lyrics, placing her within a pantheon of popular heroes who resisted oppression—from the enslaved Muslims, known as malês, who revolted and their leader Luísa Mahin to all the common, invisible “Marias” of Brazil engaged in everyday struggles. They concluded by calling the country to listen to the minorities it has long silenced: “Brasil, chegou a vez / De ouvir as Marias, Mahins, Marielles, malês.”</p> | <p style="text-align: justify;">Unlike other Brazilian cities, such as the case of Porto Alegre or São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro has not developed a tradition of partisan urban management in recent years. In the case of Rio, the Left’s relative weakness at the municipal and state levels has to do, among other reasons, with the history of brizolismo associated with Leonel Brizola and the lack of Workers’ Party (PT) roots within municipal policy. The 1982 election of Leonel Brizola of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT) as governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro deeply influenced Rio politics. A national politician, Brizola represented the labor legacy of varguismo—the ideology associated with nationalist president Getúlio Vargas—in the years after the return to democracy. As Gonçalves and Bryan McCann have shown, Brizola pioneered large-scale urban interventions in the favelas and reorganized public education in the state by democratizing access for all social sectors. At the same time, he openly questioned police violence and rejected mão dura or iron fist policies against crime, which garnered criticism from middle-class sectors, who withdrew their support. Among Brizola’s legacies are the strong influence he exerted on the Left in Rio and in the formation of a whole generation of local politicians who, after the breakup of the PDT, migrated to other parties. Unlike other left-wing parties, such as the PT or more recently the PSOL, whose social bases are predominantly middle-class, Brizola’s PDT represented the last left party with deep popular grassroots foundations in Rio de Janeiro. The issue of violence in Rio de Janeiro, especially as the drug trafficking boom dominated public debate in the city and the state’s political agenda, impeded the potential for a more reformist leftist movement of the masses. More recently, the protests that took to the streets in 2013 against rising transportation costs and the corruption associated with organizing the Olympic Games produced political disenchantment in an era of economic and institutional crisis that would help lead to the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff. New dramatic levels of violence against the poor, injustice, and impunity paled attempts to expand rights to the city. PT initiatives reduced social inequalities, but they did not question the ongoing neoliberal project. Like a house of cards, the government abandoned many of the historical struggles for urban reform, especially after extreme right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro came to power. Despite his neoliberal agenda and heavy military presence in popular neighborhoods, Bolsonaro achieved strong support in these spaces. Widespread fear of urban violence, anger against corruption in all political parties—including the PT—and a moral discourse from Evangelical churches and the more conservative sectors of the Catholic Church fed this dynamic. Despite the current profound political crisis putting Brazil’s very democracy at risk, a new generation of more combative politicians, particularly women of color, is emerging. Although she was elected with the traditional vote of the progressive middle class, Marielle Franco of the PSOL inaugurated a new way of performing as a city counselor by enacting grassroots policy in popular neighborhoods, including areas controlled by the milícia. The attempt to silence Marielle propelled new figures to enter the political scene, with many of her direct advisors winning office as state and federal legislators in the 2018 elections. Like Marielle, they are women, Black, and favela dwellers, and they carry the political practices of the city to many popular spaces. This year, the champion samba school Mangueira honored Marielle in its lyrics, placing her within a pantheon of popular heroes who resisted oppression—from the enslaved Muslims, known as malês, who revolted and their leader Luísa Mahin to all the common, invisible “Marias” of Brazil engaged in everyday struggles. They concluded by calling the country to listen to the minorities it has long silenced: “Brasil, chegou a vez / De ouvir as Marias, Mahins, Marielles, malês.”</p> | ||

== References == | |||

[[Category:Temática - Urbanização]][[Category:Milícia]][[Category:Verbetes em Inglês]] | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Categoria:Rio de Janeiro]] | |||

Edição atual tal como às 17h10min de 18 de agosto de 2023

Autores: Leandro Benmergui'[1]' e Rafael Soares Gonçalves[2][3]

Intro[editar | editar código-fonte]

Rio de Janeiro’s poor communities face increasing vulnerability as armed groups expand control of entire neighborhoods, operating illicit businesses from protection rackets to real estate, with dire consequences for local residents living under a violent parallel state.

In April 2019, two buildings collapsed in the community of Muzema, Rio de Janeiro, killing 24 people as a result of the heavy rains that hit the city during the summer. Sixteen other buildings with similar characteristics remain at risk of collapse. The municipal government has debated between eviction, demolition, and a dangerous status quo, given the appeal filed by the residents of the complex to prevent their removal. The deaths, material damage, and widespread chaos in the city as a result of the storms revealed the negligence of the municipal, state, and federal governments and the lack of consistent urban and housing policies, especially for the most impoverished sectors of the city. The Muzema tragedy, however, was not the result of natural causes: it was a product of the actions of Rio de Janeiro’s milícias, namely their urban practices and their real estate ventures. Muzema is a favela located in the west of Rio, a region under the territorial control of these milícias—parastate groups composed of police, military firefighters, and active or retired correctional officers who assert control over poor communities. The milícias are in the process of expanding and have already taken over many of the city’s favelas. They are authoritarian, and they suppress neighborhood associations and repress dissent through intimidation and murder. They offer security to residents, especially against drug trafficking and crime, as the basis for their legitimacy. In addition to these “protection” services, their businesses include selling gas cylinders, cable TV and internet, transportation services, and real estate, among other ventures. Territorial control provides them with a wealth of voters that has allowed them to elect representatives to all levels of executive power in the municipal, state, and national governments, institutionalizing their influence and guaranteeing impunity. Police investigations have linked members of the milícias with the brutal March 2018 murder of Marielle Franco, along with her driver Anderson Gomes. At the time of her death, the councilwoman, a prominent Black and LGBTQI+ activist of favela origin, had been investigating milícia practices in the favelas and their connections with politicians and members of the government. Today, Rio de Janeiro is a case study in dystopian radicalism: the milícias are advancing violently and with impunity on the urban space and daily life of Rio residents, becoming part of the state structures at the municipal, state, and federal levels, seriously threatening democratic life in Brazil.

Milícia History[editar | editar código-fonte]

The organization of para-police groups in Rio began at the end of the 1950s with the creation of the Grupo de Diligências Especiais at the initiative of the police chief of Brazil’s then-capital city. Its primary mission was the execution of criminals. Known as Esquadrões da Morte or death squads, these groups were composed of active and retired police officers. The Esquadrões extended their presence through the Baixada Fluminense on Rio’s periphery, an area that grew rapidly as a result of the allotment of lands—in many cases of dubious origins—as migrants arriving from the interior did not have access to housing in more central areas of the city. These extermination groups, known as polícia mineira, charged vendors and small business owners for protection and carried out contract killings, as sociologist Michel Misse has noted. They also had links with community and political leaders, such as Tenório Cavalcanti, the famous leader of the Baixada known as the “man in the black cape.” It was said that he hid a German machine gun nicknamed Lurdinha in his coat. In the 2003 book Dos barões ao extermínio: uma história da violência na Baixada Fluminense, sociologist José Claudio Souza Alves explains that the elimination of the rule of law and the advance of state terrorism during the 1964-1985 military dictatorship paved the way for the consolidation of death squads linked to the military police, a force created in 1967. Relations developed with other civil and political leaders who would take up positions within the structure of the state once democracy returned. The current milícias emerged based on this model. They exercise ironclad military and territorial control over the favelas located in Rio’s periphery, dominate community organizations, and extend their links with politicians and public officials, allowing them access to structures of executive, legislative, and judicial power. According to scholars Ignacio Cano and Thais Lemos Duarte, five central elements define the milícias: territorial and population control by irregular armed groups in small areas; coercion of inhabitants and local businesses; drive for individual profit; legitimizing discourses of fighting drug trafficking and establishing order and protection; and the active participation of armed state agents in positions of command. Rio das Pedras, located in Rio’s West Zone, was the first favela to fall under milícia control at the end of the 1980s. From there they expanded to other favelas of the West Zone and, later, the entire city. In Rio das Pedras, the milícia took over the residents’ association, expelling or executing its former leaders, and later it began selling its “services” to shopkeepers and the entire population of the favela. The neighborhood quickly became famous for “killing bandidos” (criminals) and ending drug trafficking. Amid a surge in drug trafficking-related violence—whether between rival factions fighting for control of the favelas or between criminal groups and the police—the general public, including many favela residents, received this rhetoric of security and order in the face of drug violence positively. Many perceived Rio das Pedras as an example of security, protection, and order. As Michelle Airam da Costa Chaves’s study on journalistic coverage of milícias shows, there have been no major police operations in communities occupied by milícia groups in recent years, reinforcing the idea that these groups are a “lesser evil” compared to drug traffickers. This idea spread in the 2000s as milícias advanced into other favelas and expelled the drug trafficking operations there, as Alba Zaluar and Isabel Siqueira Conceição have analyzed. In 2006, Rio mayor Cesar Maia even classified milícias as “community self-defense” groups against drug trafficking and as possible interlocutors with the state, since they were made up of former police officers. At that time, Rio was preparing to organize the 2007 Pan American Games, the first in a series of international mega-events that included the 2014 FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Olympic Games. For the state, these milícias promised relative calm in the favelas during the events that had the city at the center of global attention. For the middle class, forever anxious about favelas and drug trafficking—despite always needing the cheap labor favela residents provide and middle-class people being the main consumers of drugs—the milícias represented a solution rather than a problem. The press generally reproduced this positive assessment. However, in May 2008, milícias from the Batan favela kidnapped and tortured journalists from the O Dia newspaper who had been investigating their actions. From that moment, the perception of the milicas shifted to being part of organized crime and compared to mafias. Together with an escalation of violence, milícia expansion into other favelas, and the diversification of their illegal businesses, this incident provoked a change. After several frustrated attempts led by the leftist representative Marcelo Freixo of the Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL), the Rio state legislature finally opened a parliamentary investigation into the episode. Ten years later, a Datafolha investigation in conjunction with the Brazilian Public Safety Forum indicated that milícia members are more feared than traffickers, both in the communities of Rio and in the most privileged neighborhoods of the southern Rio area.

Urbanismo Miliciano[editar | editar código-fonte]

The milícia’s activities are multiple. Typically, they begin by occupying a favela and banishing traffickers. Once established, they sell protection to residents and businesses, charging security fees and ensuring control of the other areas in which they do business. Surprisingly, the milícias also divert and steal oil directly from distribution pipelines, run garbage collection operations, illegally extract sand, and conduct shrimp fishing outside the permitted period. There are reports that milícias trade narcotics directly or through agreements with certain drug trafficking factions. The real estate business is key. According to 2008 parliamentary commission investigation report on milícias, the tax on home sales varied between 10 to 50 percent of the sales’ value, in addition to the fees collected to legalize the housing or to authorize self-construction. The rapidly growing favelas offer significant profits in the informal real estate market, and the milícias have both access to the area and operational capacity. The Muzema tragedy evidenced the extent to which the milícias have invested heavily in the local informal real estate market, this time including a series of tall housing structures, a new development in the verticalization of informality. We use the concept urbanismo miliciano to describe this kind of urban intervention, which includes the illegal appropriation of public land and its allotment, mass construction of buildings, and real estate and financing operations through informal credit. Shielded by impunity or tacit consent, milícias avoid municipal controls to appropriate land and erect buildings without any supervision and without even having development plans endorsed by the relevant authorities. The lack of services and urban infrastructure, in addition to buildings’ poor construction, reproduces the vulnerability of the future “owners,” who inhabit the homes before they are finished to hedge against potential eviction or the completion of the work being blocked. Of course, this type of verticalization also occurs in other favelas, including those dominated by drug trafficking. However, the scale and logic behind the construction are different. In a large portion of the favelas, it is the residents themselves who build new floors to live in, sell, or rent, following a for-profit scheme. But they do this progressively, following a model of self-construction in accordance with the family’s needs or economic means, as anthropologist Mariana Cavalcanti has documented. From a civil engineering perspective, in many cases more construction materials and infrastructure are used than necessary. On the other hand, in the case of buildings like in Muzema, construction happens in a comprehensive way. Without any kind of urban plan, this development streamlines the construction process in a traditional way and looks to save on materials, always seeking to maximize profits. The milícia controls real estate activities and ultimately resolves conflicts between neighbors. Not all builders and sellers are necessarily members of the milícia, but they must respect the rules imposed and pay the required fees. It is very common that any and all real estate transactions be registered in the residents’ association, controlled by the milícias, through the payment of a percentage of the property value, in addition to the usual monthly rate for security services. This milícia expansion is certainly not without tensions related to the logic of a state that still must provide some kind of solution to urban problems or mediate between formal and informal sectors. The recent eradication in September 2019 of the Canal do Anil favela, for example, where the municipality intervened by strategically demolishing milícia-owned houses, demonstrated the tension between the interests of the informal real estate business of the milícia and the formal one. In this context, the role of the public defender’s office remains at a crossroads between the need to defend owners who legally purchased their properties and, in doing so, indirectly benefiting the milícia. At the same time, this year Rio’s Evangelist mayor Marcelo Crivella continued to propose further construction of housing complexes in Rio das Pedras, the first community under milícia control. These contradictions demonstrate the complexity and overlap of interests that make the question of housing and urban issues in Rio difficult to resolve.

Rio’s Dystopian Model[editar | editar código-fonte]

In a city where the constant fear of violence and consequent value of security have determined housing patterns of the middle and upper classes, we must consider how sectors lower on the social ladder seek the same standards. The viability of these real estate ventures also has to do with access to informal forms of credit and payment in installments, given the impossibility of accessing formal mortgage markets. The comparatively low cost of housing in the informal market also reflects the absence of both public mechanisms to control land values and public policy regarding social housing. Relying on the market as the only regulatory mechanism leads to spatial segregation, pushing affordable housing towards the urban periphery with lower costs and quality. Anthropologist Teresa Caldeira has highlighted the relationship between the illegal private security market, death squads, and the privatization of public space and ways of living. The same search for security that delineated the fortified enclaves of the elite in gated neighborhoods throughout Brazil now manifests in Rio’s favelas. The inhabitants who choose to buy a home in a building built illegally in a favela choose to pay the cost of daily control over their lives, as well as the extra fees to live in a seemingly safe and predictable place—even when, as happened in Muzema, torrential rains expose buildings’ poor construction quality and the state of constant vulnerability residents unprotected by the law must face. In addition to mourning their dead, many of the survivors of the collapse lost their economic investment and had to return to live with other relatives or friends in favelas in remote areas. Furthermore, the milícias control a large part of the housing complexes built by the federal social housing plan known as Minha Casa, Minha Vida. This project conceived the new popular neighborhoods in the image of gated middle-class condominiums. The milícias have forcibly interfered in these areas with the offer of private security, authoritatively organizing other dimensions of residents’ daily life. This cycle of violence dangerously degrades basic human rights principles and the democratic order itself. Undoubtedly, the presence of organized crime in the development of urban informality in Rio is as old as the city itself. We do not intend to argue against informality. The ways popular sectors access the city have always involved informal mechanisms. Historically, as Rafael Soares Gonçalves has argued, the origin and consolidation of the favelas were linked to the informalization of the real estate market through laws and urban codes that illegalized alternative forms of occupation and land tenure. In that way, informality is an urban planning regime through which the most impoverished sectors have achieved access to housing and the city itself. The precariousness of the rights and the vulnerability of favelas inhabitants—a product of the lack of official recognition of their existence—resulted in multiple political arrangements between residents, speculators, and local politicians, which in turn led to the formation and consolidation of these settlements, as Gonçalves, historian Brodwyn Fischer, and others have demonstrated. Although historically informality in the favelas has produced practices linked to organized crime and abuse, even in connection with public authorities, the current situation marks a qualitative change. The actions of the milícias represent a new dimension of the activities of parastate groups, whose central feature is precisely the exploitation of urban resources without clear forms of control by the state or local associations. Their presence in public power structures makes it highly likely that they will continue to establish themselves in key places of the state—at the local, state, and federal levels—and within urban space by selling their services, intimidating, and increasingly militarizing Rio’s geography.

Illuminating Resistance[editar | editar código-fonte]

Unlike other Brazilian cities, such as the case of Porto Alegre or São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro has not developed a tradition of partisan urban management in recent years. In the case of Rio, the Left’s relative weakness at the municipal and state levels has to do, among other reasons, with the history of brizolismo associated with Leonel Brizola and the lack of Workers’ Party (PT) roots within municipal policy. The 1982 election of Leonel Brizola of the Democratic Labor Party (PDT) as governor of the state of Rio de Janeiro deeply influenced Rio politics. A national politician, Brizola represented the labor legacy of varguismo—the ideology associated with nationalist president Getúlio Vargas—in the years after the return to democracy. As Gonçalves and Bryan McCann have shown, Brizola pioneered large-scale urban interventions in the favelas and reorganized public education in the state by democratizing access for all social sectors. At the same time, he openly questioned police violence and rejected mão dura or iron fist policies against crime, which garnered criticism from middle-class sectors, who withdrew their support. Among Brizola’s legacies are the strong influence he exerted on the Left in Rio and in the formation of a whole generation of local politicians who, after the breakup of the PDT, migrated to other parties. Unlike other left-wing parties, such as the PT or more recently the PSOL, whose social bases are predominantly middle-class, Brizola’s PDT represented the last left party with deep popular grassroots foundations in Rio de Janeiro. The issue of violence in Rio de Janeiro, especially as the drug trafficking boom dominated public debate in the city and the state’s political agenda, impeded the potential for a more reformist leftist movement of the masses. More recently, the protests that took to the streets in 2013 against rising transportation costs and the corruption associated with organizing the Olympic Games produced political disenchantment in an era of economic and institutional crisis that would help lead to the impeachment of former president Dilma Rousseff. New dramatic levels of violence against the poor, injustice, and impunity paled attempts to expand rights to the city. PT initiatives reduced social inequalities, but they did not question the ongoing neoliberal project. Like a house of cards, the government abandoned many of the historical struggles for urban reform, especially after extreme right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro came to power. Despite his neoliberal agenda and heavy military presence in popular neighborhoods, Bolsonaro achieved strong support in these spaces. Widespread fear of urban violence, anger against corruption in all political parties—including the PT—and a moral discourse from Evangelical churches and the more conservative sectors of the Catholic Church fed this dynamic. Despite the current profound political crisis putting Brazil’s very democracy at risk, a new generation of more combative politicians, particularly women of color, is emerging. Although she was elected with the traditional vote of the progressive middle class, Marielle Franco of the PSOL inaugurated a new way of performing as a city counselor by enacting grassroots policy in popular neighborhoods, including areas controlled by the milícia. The attempt to silence Marielle propelled new figures to enter the political scene, with many of her direct advisors winning office as state and federal legislators in the 2018 elections. Like Marielle, they are women, Black, and favela dwellers, and they carry the political practices of the city to many popular spaces. This year, the champion samba school Mangueira honored Marielle in its lyrics, placing her within a pantheon of popular heroes who resisted oppression—from the enslaved Muslims, known as malês, who revolted and their leader Luísa Mahin to all the common, invisible “Marias” of Brazil engaged in everyday struggles. They concluded by calling the country to listen to the minorities it has long silenced: “Brasil, chegou a vez / De ouvir as Marias, Mahins, Marielles, malês.”

References[editar | editar código-fonte]

- ↑ (Ph.D. University of Maryland) is an assistant professor in the Department of History at Purchase College, SUNY; he chairs the Department of Latin American Studies and is the director of Casa Purchase, an Outreach Center for Latin American Studies. His work is on the transnational aspects of urban and housing policies in Latin America. leandro.benmergui@purchase.edu

- ↑ (Ph.D. Université de Paris VII) is an associate professor in the Department of Social Work at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica-Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ), Brazil. He is the coordinator of the Laboratório de Estudos Urbanos e Soioambientais (LEUS) and editor of the journal O Social em Questão. He is the author of Favelas do Rio de Janeiro: História e Direito (2013). rafaelsgoncalves@yahoo.com.br

- ↑ Extraído de: NACLA Report on the Americas, 51:4, 379-385